Why financial stability is freedom

Info: This is part two of the Freelance & Prosper series, a series about how to prosper in a job that can feel very insecure and not very stable to some.

I have a lot of freedom of choice in my life these days, and it all comes from working as a freelancer. I can’t see myself ever going back to the “treadmill” of permanent employment. Not only because it’s a massive pay cut but also because I’ve yet to meet the employer who will let me work the way I do now. At this point, I’m convinced I’d go crazy after six months of employment and feel trapped because I didn’t have the option of just getting up and leaving. I realize you have that option as an employee; it’s just a lot harder than simply saying no to staying on another three months.

Financial stability is not the same as being financially independent. I am dependent on income from work, but I’m financially stable enough to go without income for a little bit. In part 1 I mentioned that I started putting money aside early in my career. I also started thinking long-term - financially - and concluded that I needed to control my expenses. Income can be hard to control as a freelancer, but my expenses are easy to control, and getting in the habit of making a budget and sticking to it seemed the easiest way to do that.

Cost of living

Your cost of living vs. income is the biggest decider on how much disposable income you have to put away to savings. Your monthly - or in my case, yearly - expenses is your burn rate. Knowing your burn rate is essential, and there are several factors to consider. I’m not a personal finance guy, so I can only share what aspects I think about. Your situation may vary.

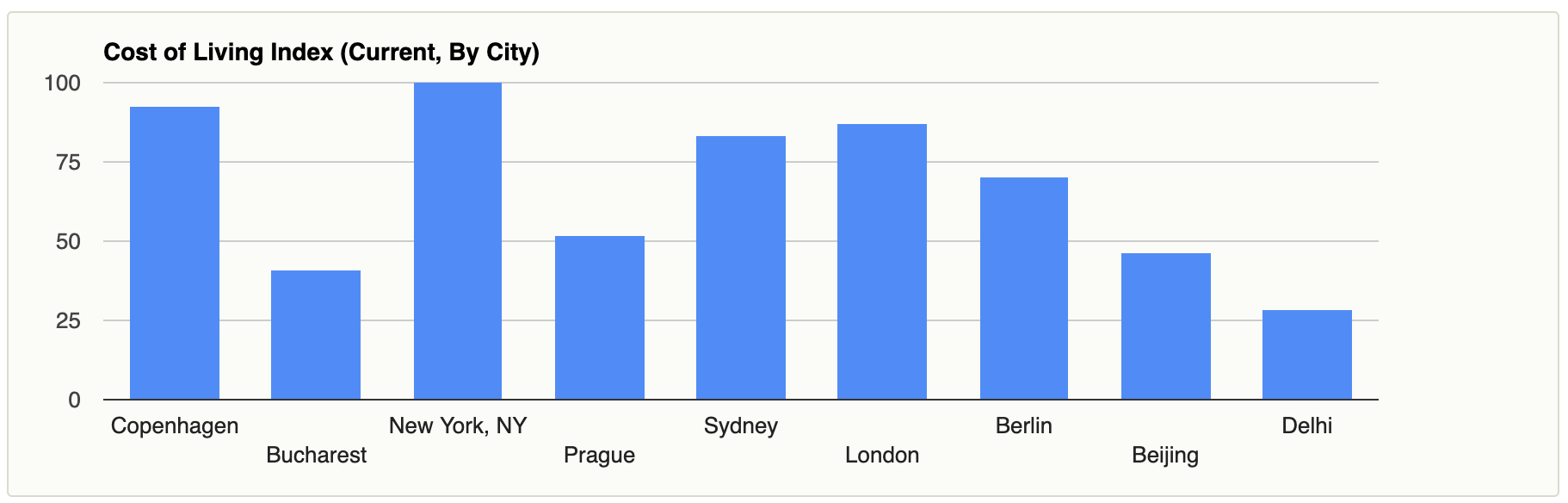

Cost of living index, 2020.

I live in Copenhagen, which has a relatively severe cost of living index. Denmark is - in general - not a cheap country compared to many other European nations, especially when it comes to what I call the bare necessities; A place to live, minimum insurance, power, heating, and basic foodstuffs. A loaf of fresh bread in Copenhagen is around €3 on average, and the average cost of a one-bedroom apartment in the city center will run you about €1500 per month. These are significant numbers because they give you some idea of what kind of budget you need. I’m not going to argue you should move because you found something cheaper, but looking at how much your current accommodations cost vs. the average gives you a basis on which to ask yourself if it’s worth it. The same thing goes for monthly expenses. Ask yourself if there are services you’re paying for you don’t need or rarely use. Then ask yourself if it’s worth it to you.

There are always cheaper alternatives to the average prices. For example, I currently live in a four-bedroom apartment in Copenhagen 10 minutes from the beach, which ran me about €1800 when I was paying on the loans, but since becoming - in effect - debt-free, it only runs me €900. It took me some time to find it, but I was in no hurry to move since I was in a cheap apartment already. I like good things like everyone else, and I don’t deny myself anything I want. A lovely loaf of fresh bread, a tender steak, a nice bottle of wine - all of these things I enjoy and feel comfortable purchasing because I know I’m spending far less on other expenses than the average.

Don’t cut things you enjoy

Over the years, I’ve learned what to cut and what not to cut. These are subjective things, which vary from person to person. I know a guy that spends well over €300 a month on coffee from a place he enjoys going to, and I would never suggest he cut that expense. If you cut things you enjoy, you experience loss, and it becomes harder to put that money aside consistently when you know you can afford something you enjoy, but you’re choosing not to, because of what? Something you want to achieve in the next decade? For an amount of money, that is likely not going to make the difference anyway. I can almost hear the argument in my head already, and it feels - to me - like the path of least resistance to do something else.

With all that said, I did go for a long time without eating out or traveling. I did that to build my nest egg, so later I could enjoy those things without worrying about the cost. From that experience, I made a set of rules (yeah, I like making rules), which make me stop and think - not prevent me from using the money.

< 1%

If something costs less than 1% of your savings, and it’s a one-time expense, don’t sweat it. It’s likely going to make no difference at the end of the day.

< 5%

If something costs more than 1% but less than 5% of your savings, consider if it’s something you need or just something you want. I’m not saying you should only buy things you need; I’m saying be clear about your motivations. Give it a few days, and if you still want it, go ahead. Often, I decide I don’t want it anyway after this short consideration.

> 5%

If something is more than 5% of your savings, it should be cause for serious consideration. I rarely spend this kind of money on anything I don’t need because the amount of money does matter in the long term. Things I’ve spent money on in this category include my home, renovations to said home, and that’s about it.

Thinking long term

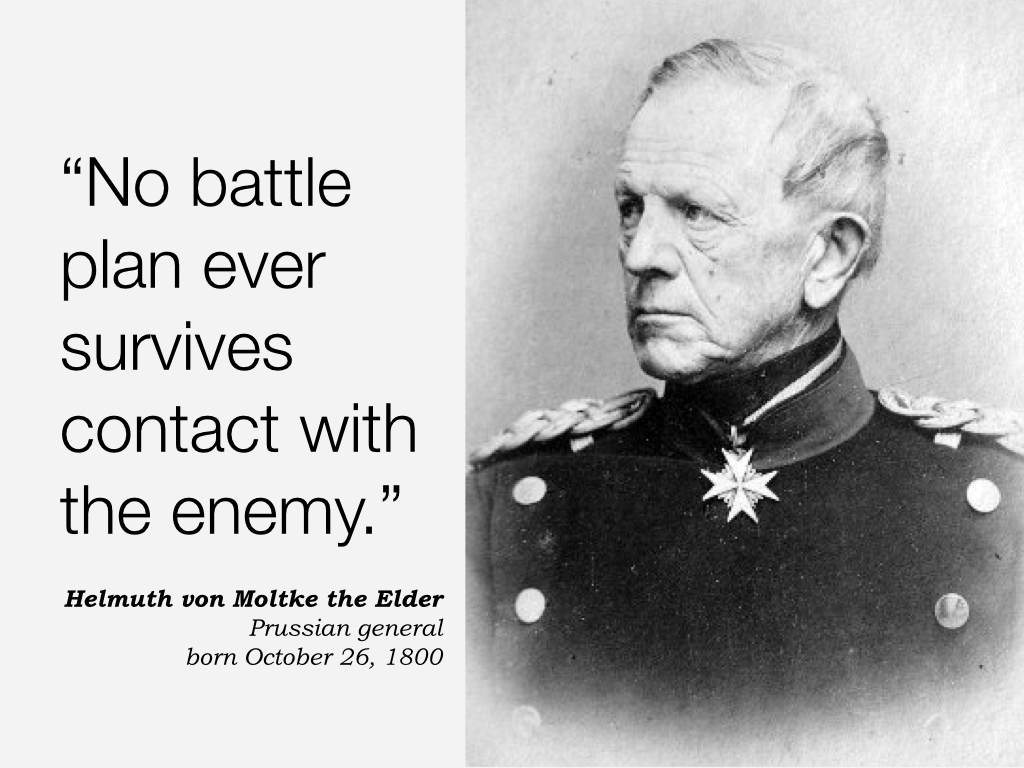

When people say they want to think long-term, I always wonder how long-term they’re thinking. When I was 18, I made a five- and ten-year plan for my life, in which I planned out my education and subsequent career path in broad strokes. The 5-year plan was as detailed as I could make it, and the ten-year plan was more broad strokes. Finish education, find a job that quickly gives me lots of experience, find an apartment, etc. These days I might call this an Agile plan because it mainly sets the direction and allows for changes. You can’t plan everything, but I’ve always felt that if you don’t have a plan, how will you achieve your goals?

How to set actionable goals

How you set goals and what you set goals for is subjective. I like to set ambitious goals - aim for the stars as they say - because it motivates me to try and move “the needle.”

Your goals should be clear. Having fuzzy goals is - as in software development - an excellent way to make sure you never reach them, so setting clear goals is essential. A goal like “retire when I’m 50” is a fuzzy goal, not because of the sentiment, but because it’s too vague. It may be what you want to achieve, but it says nothing about what you need to do to get there. It’s also a goal that is far in the future for most, and, most importantly, it describes an end to something. Focusing on something you want to start doing is more healthy and gives you something to look forward to. Goals are subjective, though. I like being a developer, so why would I make plans to stop being one?

Pillars and goals

I always align my goals with the three pillars of need because these pillars represent what I want out of my time. They are not only for my work life but also my personal life. My need to learn can be expressed as an overall intention to keep improving and a set of goals to - for example - teach myself how to code AI, travel to different countries, or challenge my natural inclination to keep to myself. The last one could have multiple objectives, just like in gaming. Taking on speaking engagements, writing posts for my website, and involving myself in different communities are examples of objectives I set for myself.

Having multiple objectives between where you are and your goal gives me something tangible to achieve, and upon reaching an objective, it feels like I’m moving towards my goal. I’ll set up an objective such as; publish a post on something every two weeks. Every time I do, I’m moving towards my goal, and that motivates me to continue. Taking on other objectives, such as involving myself in communities, comes with a compound effect because now I’m moving faster towards my goal.

Plan for changing plans

Maintain a flexible approach to your plans, and have backup plans. How well you adjust to changing circumstances is paramount, so plan for changing plans. In most cases, we are our own worst enemies when following plans - I know I am. So the approach I have is almost to gamify achieving goals to make it feel like I’m making progress. The most common reason I feel unmotivated to accomplish a goal is that I don’t seem to be making progress on it, and it seems too far away. If it seems too far away, it’s because I don’t know how to get there. As an intelligent person once said, you can’t eat an elephant in one bite; you need to take it one bite at a time.

Make a buffer

Having a financial buffer means you can even out any contract dry spells, but it also means you have the option of saying no to work you don’t want. The buffer combined with thinking long-term is your two most powerful tools. Making decisions should be based on the three pillars, because these align with my long term goals. Having a buffer means you can base your decisions on things that align with your goals rather than immediate financial needs.

Having a buffer also means I don’t need to sweat the small stuff. Is my computer becoming outdated? I’ll get a new one. Do I need to take an in-person meeting with a client in Norway? Not a problem. Do I want to take three months to build a prototype for an idea? Again, not a problem.

Should you invest your buffer?

Sizing your buffer right is very subjective. The way I did it - at first - was by looking at how many contracts I would likely get each year. A few years later, I felt like I knew my average annual income, so I told myself I wanted to have two years of no income as my buffer. I dipped into those savings when I moved to Copenhagen. Beyond that, they have been sitting in the bank.

I have considered investing, and I did for a short time before moving to Copenhagen. There are pros and cons to investing, and I’ve yet to decide to do it again. On the one side, your buffer gets tied up, and it can be costly to get it out quickly if you need to. Whether you invest personally through an app or banks, be aware that pulling your money out quickly is never “free.” Sometimes there are penalty fees, the stock could have taken a downward swing and has yet to recover, and several other things could be costing you money. Investing is long-term thinking, though, because, to be relatively immune to swings and negative trends, you should always consider the very long term, +10 years at the minimum. Ideally, you invest in something which pays around 8% annual returns, and your money will double every ten years. This return rate is the FIRE movement rule of thumb for investments, and I’ll admit it appeals to me. But this post isn’t about financial independence.

Time buffer

In the interest of having a healthy work-life balance, I want to mention that your financial buffer is not the only buffer you should maintain. I always try and keep a month of downtime between contracts because it gives me time to decompress and refocus on my next contract. If I’m on a long contract, I’m chronically bad at taking time off during the contract. I like to say that I work when there is work, and I relax when there isn’t. Historically, this approach has led me to burnout, so I can’t recommend it. I’m still trying to find a good balance, and it starts by being open about vacation plans when it turns out the contract is longer than three months. I’ll get more into downtime and the time buffer in part 3 of this series.

“Fuck you” money

At a conference - some years ago - I was introduced to another freelancer, who told me about his “fuck you” fund. He’d set up a savings account for suing clients who didn’t pay or clients who attempted to sue him for any nonsense. He was an American, and that legal system always seemed a little riskier to me, but I generally liked the idea. As time went on, it just became part of my regular buffer because I realized that the whole buffer fund was one big “fuck you” fund. Not because I wanted to use all of it to sue people, but because I was saying “fuck you” to the idea of being a slave to a job and employers in general.

Hopefully, it goes without saying that the “fuck you” fund is not indicative of your communication strategy with a client. Instead, it’s about not having to stay longer than you want to. The proverbial “fuck you” - for me - becomes saying no to extensions to my contract, even when offered. I’ve done this three times so far, and in all instances, it was the best decision for me. Burnout is real. I’ve been there. Working 12-16 hour days, six days a week for months, until finally you no longer want to look at your computer, let alone talk to your client. There is only one response to jobs like that; Fuck you.

Always another contract

Thinking about your cost of living and knowing your “burn rate” enables you to start trimming your expenses so you can build savings. When you have savings, you can begin to make long-term plans and goals. Those goals should be specific enough to set up objectives to reach the goal and align with your personal need pillars. Your savings is also your buffer for dry spells, and while buffer sizes are subjective, it’s always a good idea to have one. So when you’re thinking about using your savings, consider the <1%, <5%, and >5% rules and ask yourself: “Do I need it?”. If you’re making good money, and your buffer is where you want it, you spend money on all the stuff you trimmed or on things that align with your goals. It’s that easy. If you consider all of these things, there is always another contract out there.

Fear comes from uncertainty. I’m confident I can go on living the way I do for years without income. I know that my burn rate is adjusted to my buffer size, enabling me to maintain my lifestyle. I have experienced ups and downs, but I’ve never gone more than a few months without being offered a contract because I follow the “more than one, less than five rule”.

I’ve planned for contingencies to continue this lifestyle as best I can, so I am no longer uncertain that I can. That is why financial stability is freedom.

Key takeaways

- Think about your cost of living vs savings (Your burn rate)

- Consider making your own version of <1%, <5%, and >5%

- Think long term. Set goals according to your need pillars, and plan for changing plans.

- Have a buffer, both financial and in your life. Burnout is real.

- Use your buffer to walk away from bad situations.

- There is always going to be another contract.